Welcome to STChM Modern, a curated collection dedicated to the representation of non-existent artists. This platform provides a space for fictional creators to be formally acknowledged within the STChM framework. All intellectual property and potential commercial outcomes derived from these conceptual works remain the exclusive rights of STChM. Non-existent artists seeking representation within STChM Modern are invited to submit their applications for consideration

FEATURED ARTIST

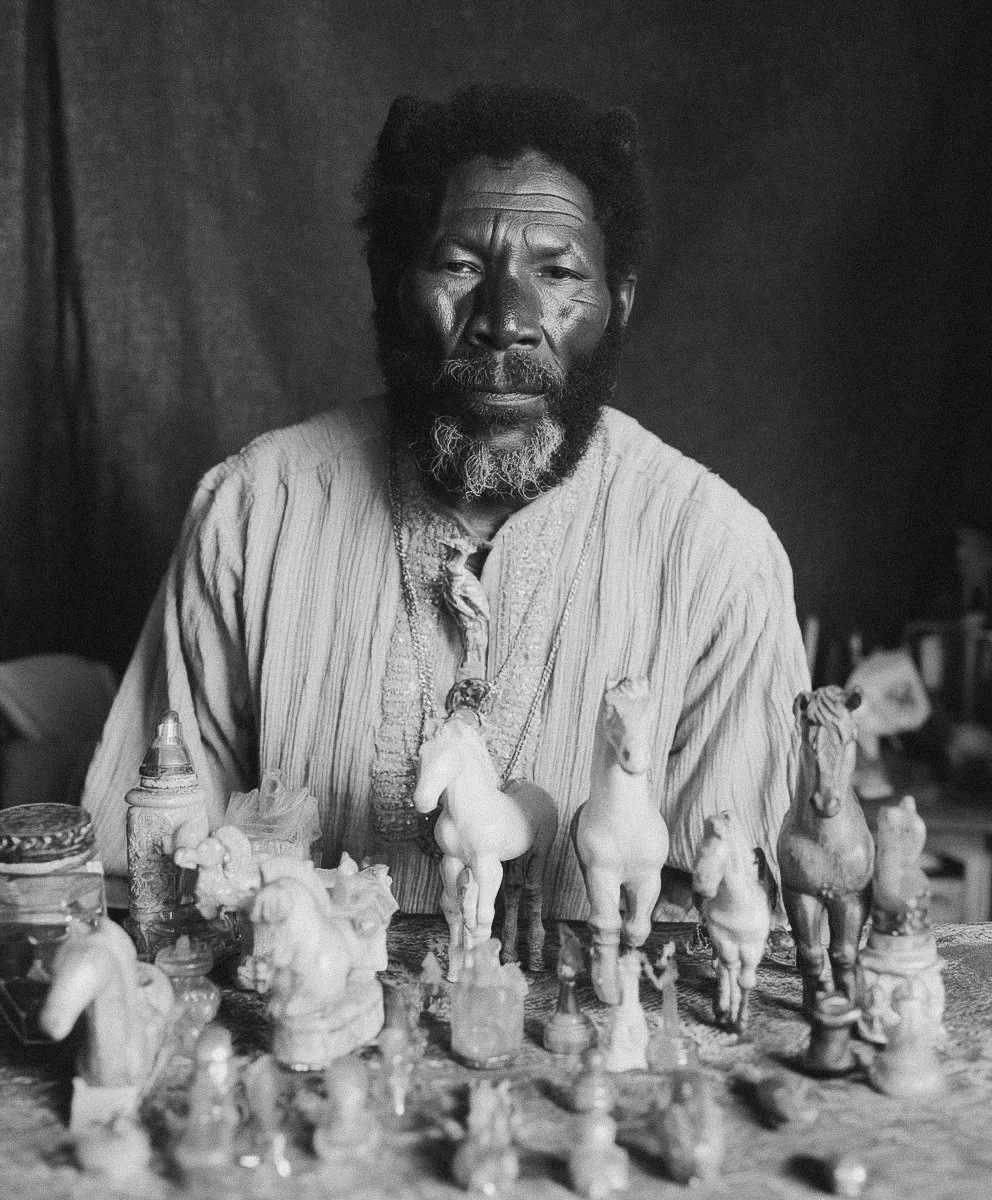

LEOPOLD

Infinite Repetition of the Leopold Dream

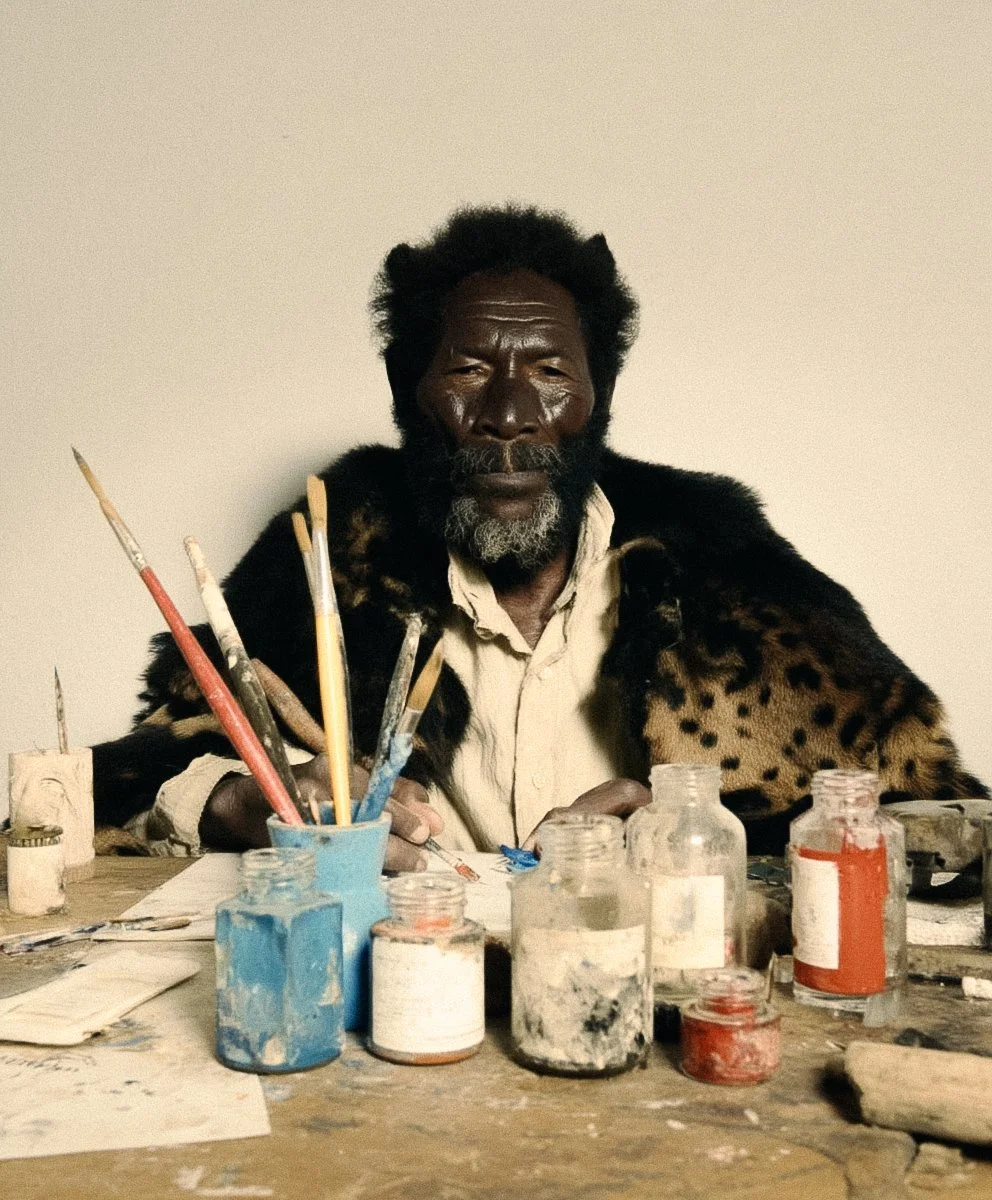

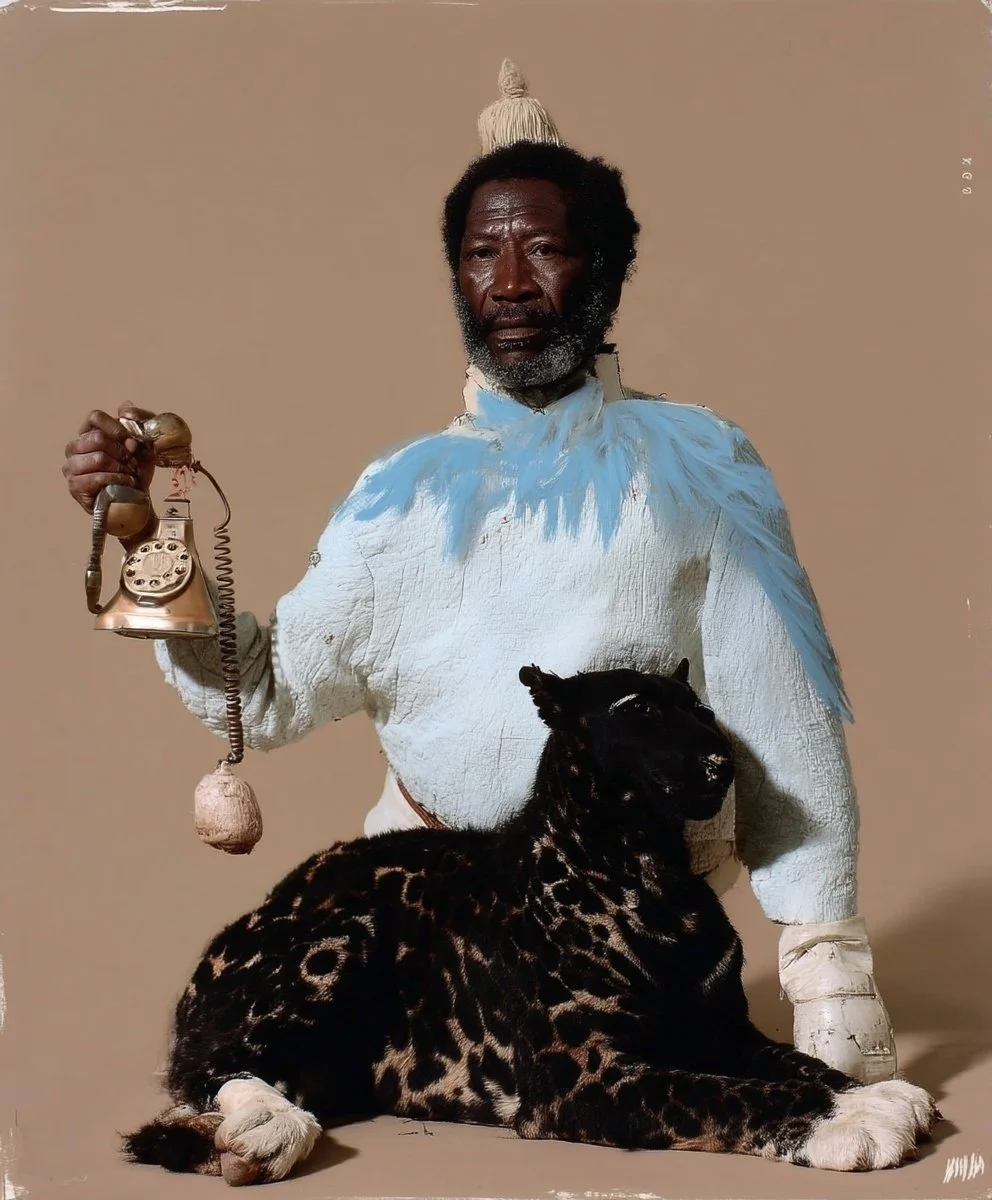

To speak of Leopold is to enter into a dialectic of recursion and rupture, a practice that oscillates between ethnographic immediacy and the metaphysical repetition that characterizes the modernist avant-garde. Born in the remote highlands of Papua New Guinea, Leopold has built an entire oeuvre around a singular dream image: he and his father, astride a horse, locked in the suspended moment of encounter with a leopard’s attack. This obsessive motif—iterated, revisited, and never exhausted—positions Leopold in a genealogy that stretches from Giacometti’s existential elongations to the serial interrogations of On Kawara, from the fatalistic iconographies of Francis Bacon to the mythic cyclicality of Anselm Kiefer.

What is at stake is not merely the content of the dream but the mechanics of its repetition. Leopold paints three to four canvases annually, each a re-entry into the same primal tableau. The gesture recalls Deleuze’s theorization of repetition as difference—the impossibility of exact recurrence, the inevitable emergence of variance within sameness. Every horse, every leopard, every paternal silhouette is simultaneously identical and altered, producing a corpus that functions less as narrative than as liturgical chant. To look at a Leopold canvas is to witness the persistence of an image haunted by its own incompleteness.

Crucially, Leopold’s formal language refuses to resolve into a single stylistic register. His faces—father, son, leopard alike—are rendered with startling hyperrealism, each pore and wrinkle meticulously articulated, as though to anchor the dream in fleshly undeniability. Yet this precision is countered by passages of looseness, almost naïve in execution: a horse’s flank reduced to a gestural wash, a leopard’s spotted pelt collapsing into childlike pattern. This oscillation destabilizes the viewer’s reading, producing a simultaneity of presence and rupture, control and abandon. It is precisely this tension—between realism’s gravity and naiveté’s volatility—that makes the dream both credible and elusive.

In the art world, Leopold’s work has become over-determined, absorbed into a hermeneutic machine that insists upon allegory. Critics perceive the leopard as colonial trauma, the horse as the ambivalent vector of modernity, the father as patriarchal rupture, the son as fractured subjectivity. His canvases have been placed in discursive dialogue with Kara Walker’s silhouettes, with Adrian Piper’s strategies of self-reflexive repetition, even with Richter’s blurred historiographies. For these audiences, the dream is never simply a dream but an allegorical cipher, a code to be unpacked within the lexicon of postcolonial critique and psychoanalytic archetype.

And yet, Leopold himself resists this scaffolding. He speaks of the dream not as metaphor but as lived continuity, as the nightly threshold between sleep and waking. Before bed, he repeats his incantation—the horse runs, the leopard comes, the father falls, the son remembers—not as art, not as theory, but as invocation. His project is not the monumentalizing of trauma but the intimate survival of memory. It is this gap, between the artist’s elemental simplicity and the elite’s discursive inflation, that gives Leopold’s practice its uncanny force.

Leopold’s dream paintings thus inhabit a paradox: hyperlocal yet universal, naïve yet strategically resistant, primitive only in the sense of originary. They carry within them the same tension that animates Gauguin’s mythopoetic Tahiti, Basquiat’s ecstatic palimpsests, and Kentridge’s animated allegories of South African rupture. Yet unlike these figures, Leopold collapses symbol into ritual, dream into discipline. His leopard does not stand for anything. It arrives. Always it arrives. And in this endless arrival lies the untranslatable essence of his work.

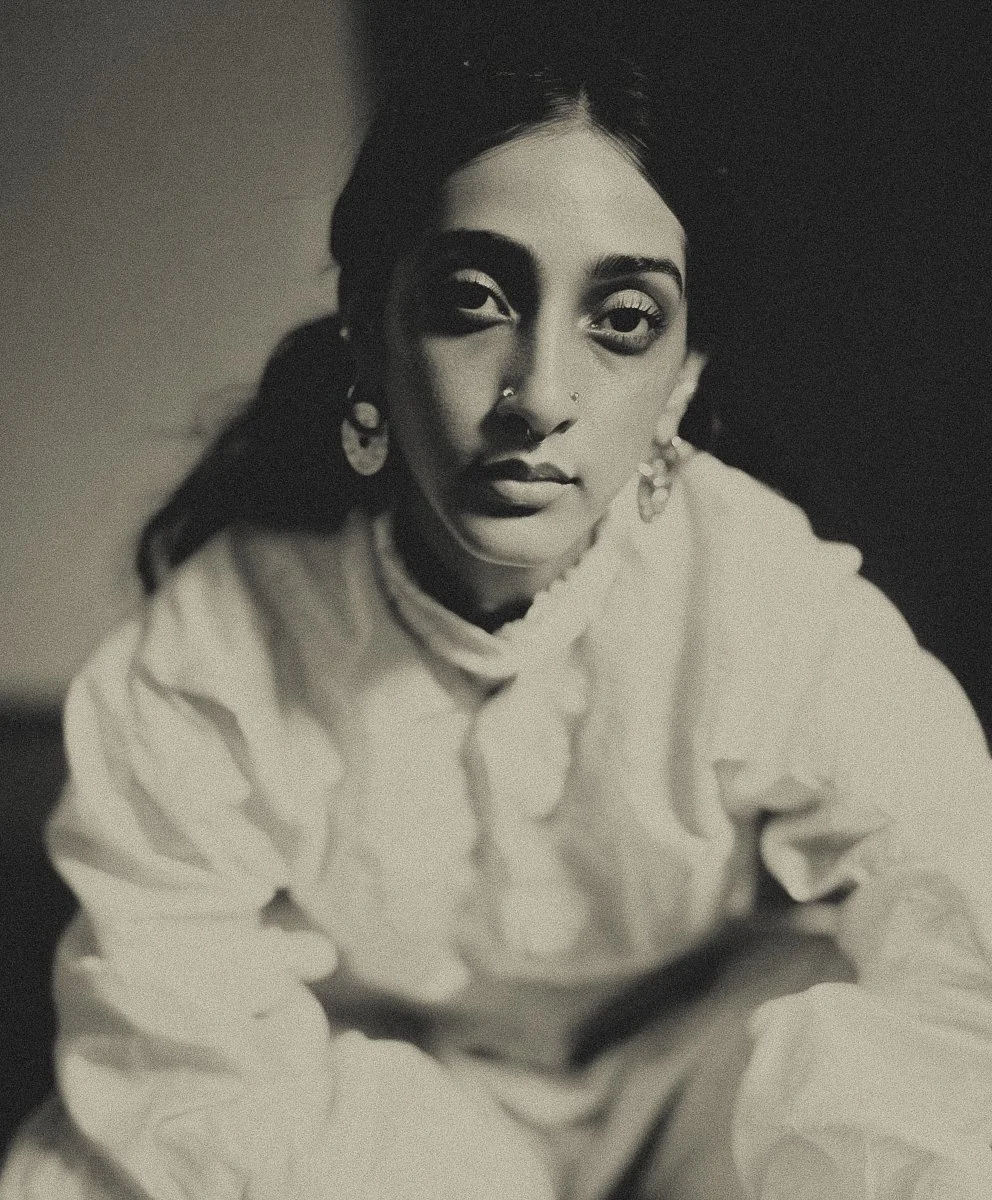

DASA KAVI

Fragile Ceramics

Born in Delhi in 1997, Dasa Kavi is a ceramic artist whose work interrogates the fragile yet enduring legacies of colonial aesthetics within modern South Asian material culture. Drawing on her background in porcelain sculpture and pottery, Kavi explores the tension between delicacy and violence inherent in the decorative arts introduced during British rule. Her practice is heavily influenced by old English crockery design—ornate floral patterns, blue-and-white motifs, and gilded embellishments—recontextualised into contemporary forms such as her renowned porcelain sneaker sculptures.

Through her art, Kavi critiques the insidious ways colonial decoration infiltrated upper-class Indian homes, not merely as aesthetic influence but as a tool of political subjugation, softening resistance and reshaping cultural aspiration. Her research extends across South and Southeast Asia, tracing parallel patterns in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Japan, revealing how decorative indoctrination often accompanied economic and political domination.

Known for her provocative performance installations, Kavi often infiltrates her own exhibitions dressed as a colonial British soldier, ceremonially destroying her creations in acts of deliberate rupture. This gesture embodies her belief that the ongoing tyranny of empire persists through unexamined aesthetic heritage. Her work invites audiences to reflect on what beauty conceals—and what liberation requires us to break.